The Power of Practice

Game 6 of the 2013 NBA finals was one of the best games in basketball history. The Miami Heat entered the game behind 3-2 to the San Antonio Spurs in the best of seven series. The entire game was close, with the lead seesawing between the teams until the Spurs took control in the last two minutes. With 28 seconds left, Manu Ginobli sank a free throw to put the Spurs up 5 points.

Bill Simmons recounts his experience watching this part of the game:

“During that now-fateful timeout with San Antonio up five, Jalen Rose and I watched NBA officials wheel the Larry O’Brien Trophy into the runway to our right. It couldn’t have been farther than 15 feet from us. We watched security guards assume positions around the court, and we watched Heat employees hastily sticking up yellow rope around the courtside seats. Like they were cordoning off a homicide scene. Even after LeBron’s second-gasp 3, I still thought we were going home. Some Heat fans had already trickled out. We watched them leave in disbelief.”

The game seemed over for all intents and purposes. What followed was an improbable and frantic finish culminating with this incredible Ray Allen 3 pointer that would send the game into overtime.

Everything about this shot is remarkable. The coolness under pressure. Allen’s mental awareness that he had to shoot a 3 for the Heat to have a chance. The balance to avoid falling out of bounds while dribbling backward, and the presence of mind to make sure that both feet were completely behind the line before shooting. This iconic play was a shining moment for one of the game’s all-time greatest shooters. We all get to see the amazing shot, but that shot was only possible because of the thousands of hours of training and practice that preceded it. Allen was once asked about how he became such a great shooter and said:

“I’ve argued this with a lot of people in my life. When people say God blessed me with a beautiful jump shot, it really pisses me off. I tell those people, ‘Don’t undermine the work I’ve put in every day.’ Not some days. Every day. Ask anyone who has been on a team with me who shoots the most. Go back to Seattle and Milwaukee and ask them. The answer is me — not because it’s a competition, but because that’s how I prepare.”

A Note on Talent

I think Allen’s answer is a powerful insight into how we can unlock the highest levels of achievement. His point is not that he has a lack of God-given talent but that his jump shot is largely the result of countless hours of practice. There are likely thousands of people with a comparable amount of natural talent as Ray Allen. Still, only a handful have honed their ability to shoot a basketball to such an elite level.

In his book, Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell examines what enables some people to achieve at remarkable levels. It is always difficult to tease apart talent and practice to find how much each had a role in a person’s success.

One of Gladwell’s more compelling examples is students who have successfully gained admittance to a top music school. Without a doubt, there is a relatively high level of required talent to be admitted to a school like Juilliard. Once a student achieved admission, Gladwell wondered, what was the biggest leading indicator of future success? Fortunately, the data paints a clear picture:

“Once a musician has enough ability to get into a top music school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it. And what’s more, the people at the very top don’t work just harder or even much harder than everyone else. They work much, much harder.”

Successful musicians are forged from a combination of natural talent and exceptional practice ethic. In some fields, the natural talent required to succeed is a high bar. The NBA only has around 500 active players at any given point in time. Even if you include international professional basketball leagues, there are only a few thousand professional basketball jobs available at any given point in time. As a result, the amount of natural physical gifting needed is relatively high. If you are 5’6″ tall, it’s borderline impossible to have a career playing professional basketball no matter how hard you practice.

In contrast, one of the great things about entrepreneurship is that the world economy needs millions of business owners. Countless people possess the natural aptitude and talent required to be an entrepreneur. Creating a business doesn’t hinge on how you look, where you were born, or what level of education you received. Instead, just like Ray Allen’s jump shot, success in entrepreneurship is largely about mindset and a willingness to put in the practice.

Practice Cultivates Talent

Recently I have been listening to the audio version of the outstanding book, The Body, by Phil Bryson. In the chapter on how our body responds to the food that we eat, Bryson notes:

“By whatever means you measure it, we are pretty good at removing energy from food. Not because we have an especially dynamic metabolism but because of a trick we learned a very long time ago – cooking…It is widely believed now that cooked food gave us the energy to grow big brains and the leisure to put them to use…the few plants we can eat are the ones we know as vegetables…but we can benefit from a lot more foods by cooking them. A cooked potato, for example, is 20 times more digestible than a raw one.”

Cooking exponentially expands the number of things that we can eat. It protects us from harmful diseases and bacteria. It changes the texture and taste of food to make it more appetizing. It even increases the amount of nutrition that we derive from food. Without cooking, our body would require us to spend our entire day eating in our quest to get enough calories. But what does cooking have to do with entrepreneurship and practice?

In the same way that cooking cultivates and enhances food, practice cultivates and enhances our natural talents and abilities. Practice unlocks our full potential and amplifies our effectiveness, but it requires a great deal of time and commitment.

For example, one study of 20-year-old violinists divided them into three talent groups based on their conservatory teachers’ scores. Those judged “best” had averaged 10,000 hours of deliberate practice since taking up the violin. Those judged “better” averaged 7,500 hours. And those judged “good” averaged 5,000 hours.

One thing that is worth noting: Considering their age, all of these violinists had spent an incredible number of hours practicing. If you assume these students began playing violin at age 5, then 10,000 hours of practice had required 11% of their life to be dedicated to training!

Fixed Mindset vs. Growth Mindset

Our mindset profoundly influences how we view practice. In her classic work, Mindset, Carol Dweck makes a compelling case that most people can be categorized as having a predominantly “Fixed Mindset” or a “Growth Mindset.”

Fixed mindset people believe that the talents and abilities we are born with define what we can do. The idea of practice is somewhat antithetical to this self-view because your abilities are almost exclusively the result of your natural abilities. Fixed mindset people are more easily discouraged by setbacks, take feedback poorly, and view exertion of effort as proof that someone does not have talent in that area. Challenges are, therefore, something to be avoided.

In contrast, the growth mindset is characterized by a fundamental belief that our capabilities can expand and grow over time with dedication and practice. It attributes our skills to hard work and persistently working through challenges. This belief actively seeks out feedback and would assert that effort will be necessary for any significant accomplishment.

Dweck illustrates how powerful a growth mindset can be through several examples. One of the most compelling is through art. Drawing is widely considered to require a good deal of natural artistic ability. Still, even a small amount of regular practice by someone with a growth mindset can make a remarkable difference.

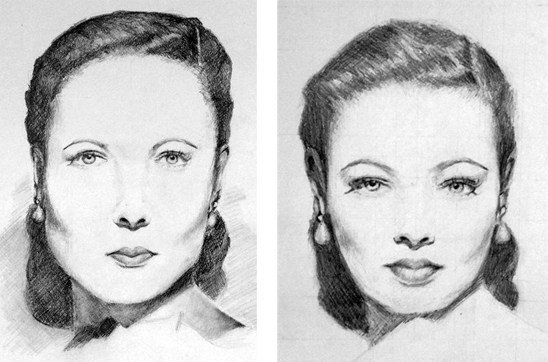

Below is an example of a before and after picture one artist produced from just a few hours of practice and instruction.

One artist’s initial drawing compared to a drawing after a 12 lesson course.

Practical Application

Entrepreneurship requires a growth mindset. Over the past 12 years, I have been fortunate to be a part of co-founding several businesses. One of the best parts is the immense amount of practice and learning in a new company.

Running a business requires being able to execute at a reasonable level in a lot of different areas. Below are some of the many needed skills that come to mind:

Recruiting

Casting Vision

Crafting Strategy

Negotiating

Motivating

Selling

Establishing Culture

Strategically Quitting

Our natural giftings and personalities give us a different base level of competence in these areas. However, no matter what our starting point, excellence is impossible without a tremendous amount of practice. Here are 5 tangible suggestions of how to apply this in your life:

1) Openness to feedback. There is a reason that the best golfers in the world still have a swing coach. No matter what level of performance we reach continued growth requires feedback. One of the ways that I grew the most in my teenage years was through being a part of basketball and track teams. Teams provide a context where others can observe your behavior, your attitude, and your habits. Your teammates become the single best place to get honest and vital feedback.

I have found that it is not easy to get others to share candid feedback, especially with a superior. To have a feedback-rich environment, you must continually ask for feedback from others instead of assuming that they will offer it if there is a way that you can improve. When you do get critical/constructive feedback, listen and seek to understand instead of responding defensively. Responding negatively to feedback communicates that you are not really open to feedback and that sharing it with you should be avoided in the future. Do people feel comfortable sharing feedback with you?

2) Root out fixed mindset thinking. Although you can generally categorize people as having a growth mindset or fixed mindset, the reality is that all of us have at least some of both. I tend to lean pretty heavily towards having a growth mindset, but there are areas of my life like music and foreign language where I am prone to fixed mindset thinking. In general, the less natural talent I have in an area, the more tempting it is for me to have a fixed mindset. What are the areas in your life that you are living with a fixed mindset?

3) Focus on process over results. Results orientated people are primarily motivated by outcomes. For example, “I will practice piano every day so that I can win the talent show in the spring.” Practice is a means to an end. In contrast, process-oriented people are primarily motivated by achieving a higher level of intrinsic skill at a particular endeavor. For example, “I will practice piano every day because I get joy from playing beautiful music. I want to know how beautifully I can play this instrument.” At some point, our ability to persist in practice has to be based on something deeper than results. It requires that we intrinsically love the process of finding out what we are capable of. Where are you more results-oriented than process-oriented?

4) Be picky in what you practice. Recent psychological experiments have shown that our brains are not able to multi-task. Unsurprisingly, we are also unable to practice many things simultaneously. Choosing judiciously where to focus our time creates the opportunity to invest meaningfully in the areas where we most want to grow. Are you trying to grow in too many areas at the same time? What are the most important areas for you to be growing right now?

What area of your life do you want to focus on practicing the most over the coming year?